SAND (Science and non-duality) is a unique conference that blends hard science with quite a bit of mysticism. I’m already in trouble because the essence of non-dual philosophy is that mysticism and science are one and the same (whole) and not two things (dual). However the SAND community is a very inclusive crowd so being “in trouble” is really not something you’d worry about. It simply generates very interesting dinner table conversations. This spirit is very unlike hard science communities which can be very harsh on non-conformists new ideas. So at SAND you are perfectly free to put forward slightly nutty ideas (I certainly was) and also tell others you thing they are talking non-sense without any worry you will offend or generate bad Karma. The format has a random nature to it. Some talk titles are very descriptive and you get what it says on the tin but other talks are – as Forest Gump would say – a box of chocolates. You might see one of the driest talks of your life and you might open an entirely new vista on your thinking and thats just in the morning before lunch. I had a great time, gave my poster talk at least 80 times (sorry if you were the one on the stand next to mine) and met some really nice people I will form friendships with for the rest of my life.

It’s a familiar theme. From Terminator to Star Wars, from AI to District 9, science fiction films have forever pitted plucky emotional humans against evil genius super-villains.

But are we now beginning to see a change? This weekend two British films will compete for the Best Film and Best Actor BAFTAs, both focussing on British scientists, who are prominent in the debate currently raging about artificial intelligence.

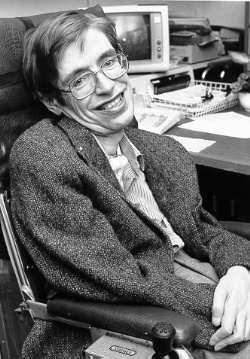

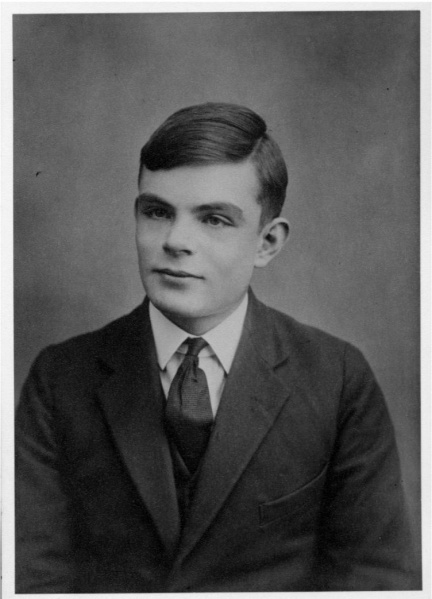

Hawking, (Eddie Redmayne, The Theory of Everything), may have shared very little in common, scientifically, with Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game) but, with dashing leading men acting out their achievements on screen, this could be about to herald a change in the portrayal of science on film.

Whilst silver screen scientists have been characterised by nerdishness, zany outfits and haphazard accidents with inventions, (think Back To The Future) these two films, like A Beautiful Mind before them, are sensitive portrayals of genius, looking both at the achievements and the men behind them.

So if we are beginning to shake off the cartoonish view of the scientist, what of Hollywood’s other source of compelling stereotypes – the robot? Artificial intelligence has provided the inspiration for some of Hollywood’s most famous, and most menacing, villains: think HAL in 2001, Joshua in War Games or Agent Smith in The Matrix.

But, we have begun to see a change in attitudes to artificial intelligence. Robot and Frank, released last year, was a heart-warming portrayal of how a robot worked alongside his elderly “owner” to mastermind a robbery while Disney’s Oscar-nominated animation Big Hero 6 has as its lovable hero a plus-size, inflatable robot called Baymax.

What of wider public attitudes? Recently we have seen a great deal of angst in the press about the dangers of artificial intelligence (AI) and whether robots will take over the world. Hawking along with many modern physicists has been outspoken about the dangers of AI. He is a founding member of the Center for the Future, which recently received a $10m grant from Elon Musk.

The group recently composed an open letter to politicians, not so much focused on the potential for world domination but on the profound changes to the economy such machines will bring.

Turing started the artificial intelligence debate by inventing the computer. The imitation game, which we now call ‘the Turing Test’ was proposed in a famous paper he wrote ‘Can Machines Think?’ and provides a test for whether we have achieved AI. He died too young to see the explosive growth in computational power we are experiencing today but he speculated extensively about how far computers could go.

Turing thought they would have mastered intelligent thought by now, but as we have discovered AI is a hard problem. If we revise Turing’s calculation using data from IBMs latest thinking machine, ’SyNAPSE’, computers will reach parity with the human brain in mid 2053. This is alarmingly soon – just over one generation – which is why the AI debate has suddenly come to the fore.

The potential for AI is perhaps the greatest questions of the modern age. If computers reach parity with humans will this bring great wealth and prosperity, automating away all the drudgery from the modern world or will it, as Steve Wozniak remarked, relegate humans to the role of pets as our computers become the dominant intelligence on the planet.

For my part I think there’s one insurmountable problem for computers to overcome if they wanted to match humans; our capacity for creativity. When Turing invented the computer he also stated a limit on its ultimate power.

Azimov’s famous laws of robotics need one more rule. “A robot may not solve or cause to be solved a puzzle for which it has not already been given a method to solve it.”

Despite computers fabulous capacity to crunch numbers they can not come up with new things. They can only extend and generalise ideas that have been programmed into them. They do this amazing well and can sometimes fool us into thinking they are intelligent but they don’t have the ability to think freely: They are programmed.

We are not going to see an innovative screen play, a breath taking artistic work or solution a great mathematical puzzle signed, iRobot.

These things are the domain of creative human minds a far more complex and subtle machine than any computer so far imagined. Computers can help us with creativity, rendering Disney Pixar movies and helping us process words but they will not come up with the concepts in the first place.

It really comes down to understanding the nature of thinking which is beautifully summed up by another founding father of the computers.

“The question of whether computers can think is just like the question of whether submarines can swim.”

Edgar Dijkstra

James Tagg is an inventor and entrepreneur. A pioneer of touch screen technology he has founded several companies including Truphone, the world’s first global mobile network.

James Tagg is an inventor and entrepreneur. A pioneer of touch screen technology he has founded several companies including Truphone, the world’s first global mobile network.

His book ‘Are the Androids Dreaming Yet? Our Amazing Brain and the enigma of Human Communication, Creativity and Free Will. (Hurst Farm Books, Feb 2015) looks at the history and science of information and argues humans are a different type of thinking machine able to create and exhibit free will.

Originally posted on the Truphone blog.

About this time each year people around the world settle down to think about the year ahead and what they could do better. In China, New Year waits until the New Moon of the first full lunar month – sometime between January 21st and February 21st, while in other countries, the year can turn over as late as autumn.

But, for most of us, New Year is the 1st of January, marked by a holiday to recover from the excesses we promise never to repeat… All this resolving: I will give up alcohol, I will exercise more, I will phone my mother – assumes we choose between what we do and don’t do. What’s the point of making a New Year’s resolution if free will does not exist? You’re going to do what you’re going to do anyway, right?

But, what is the evidence for free will? Does it really exist?

Many modern philosophers tell us free will is an illusion, that when we make a resolution we have the feeling it was freely made. But in truth we were always going to make that resolution, and we were also destined to break it. The laws of physics ensure cause and effect apply. The ‘effect’ of making some choice was really ‘caused’ by some previous event and that event caused by an event before it and so on, right back to the big bang. Our Universe is just one big clockwork mechanism and we are but a cog within it.

Just recently, a new breed of philosophers, actually mathematicians and physicists led by John Conway, have begun piecing together the science of free will. They say our Universe appears to be composed of particles that do not behave in pre-determined ways. Conway and Kochen wrote a paper in 2014 explaining how this comes about, and arguing that because the little particles that we’re made of are free, so are we.

So, as you finish off the last of the leftover chocolates and mince pies and head to the gym, be aware that what you decide might be really important, the future of our Universe depends upon it. We cause the Universe. The Universe does not cause us. If your mind goes to pondering these deep questions at this time of year – free will, creativity, inventing – I’m letting you know that mine does too.

(And now a bit of a plug, sorry.)

Five years ago I resolved to write a book about these things and, amazingly, followed through on it! The book, Are the Androids Dreaming Yet? is available now on Amazon in hardback, paperback and Kindle and on the Apple iBooks store. Signed copies can be obtained by request from my website: http://www.jamestagg.com.

ABOUT THE BOOK:

Many scientists think we have a tenuous hold on the title, “most intelligent being on the planet”. They think it’s just a matter of time before computers become smarter than us, and then what? This book charts a journey through the science of information, from the origins of language and logic, to the frontiers of modern physics. From Lewis Carroll’s logic puzzles, through Alan Turing and his work on Enigma and the imitation game, to John Bell’s inequality, and finally the Conway-Kochen ‘Free Will’ Theorem. How do the laws of physics give us our creativity, our rich experience of communication and, especially, our free will?

In my last post I talked about controlling video games with your brainwaves and the new field of Brain Computer Interfaces, ‘BCIs’. But why not run the process in reverse and have the computer modulate your brain waves?

Imagine hooking up to Call of Duty and having the game stimulate the pain centers when you get shot, for example. Not my favorite idea as I’m not very good at that game – I’d probably prefer to end a long day at the office by plugging in to a meditation machine and stimulating my calming centers.

These ideas are now made possible and companies exist which are engaged in bringing them to life – though, for ethical reasons, no one has yet proposed targeting the pain centers!

As is often the case, the open source community was first to experiment with these brain induction technologies – and there are websites out there explaining how to wire your brain up to a 9-volt battery and induce currents within it. I’ll not post the links and I’d advise against trying them unless you have a degree in electronics because there’s a risk you’ll end up with second-degree burns – but the basic technology appears perfectly safe. You can already buy a device in the US called foc.us, which claims to improve your gaming performance.

The next wave of startups has put a lot of research behind their products and at the Conciousness Conference I caught up with Jamie Tyler, CSO of Thync. I tried the Thync prototype out on Dr. Gino Yu, Associate Professor and Director of Digital Entertainment and Game Development at the school of Design, Hong Kong – a man with a very cool job title. The device works by allowing users to bias their brainwaves towards desireable mental states. We set out to calm down an agitated Dr. Yu.

It turns out, Dr. Yu doesn’t need a stressful day to get agitated – he just needs someone to talk to him about one of his passions. The Thync device is held in place with a fetching head band – not part of his usual wardrobe – and controlled with an app. You can see the effect for yourself in the pictures below.

The commercial launch of the Thync device is slated for early 2015, subject to all the appropriate safety testing and approvals.

Originally posted on the Truphone blog

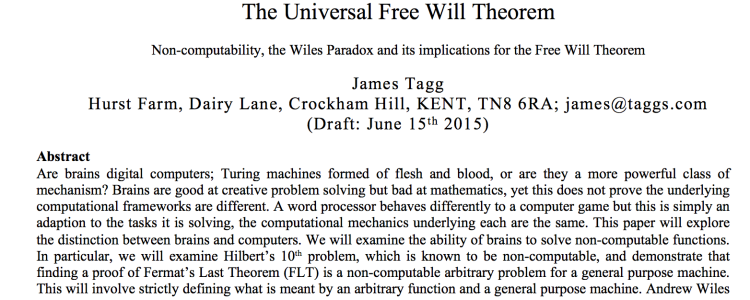

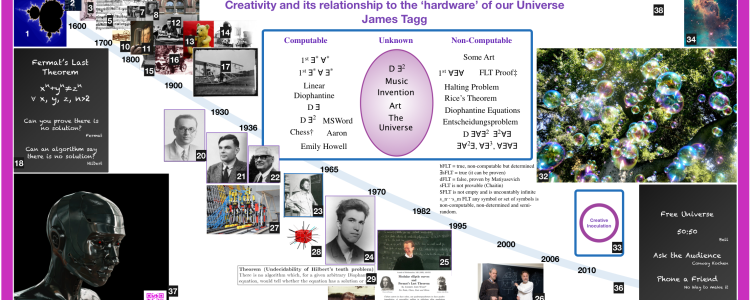

Free Will Universe Paper Text PDF I’m posting the first draft of my paper. The paper argues the general creative process is non-computable. It’s quite mathematical to start and becomes more physical towards the end. In the middle I use Andrew Wiles proof of Fermat’s last theorem to generate a piece of music that could not exit if the Universe were entirely computational.

| Index | Title: | Creator | Rights | Clearance Basis |

| 1 | Fractal | Wolfgang Beyer | Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 | Wikicommons |

| 2 | DaVinchi Flying machine | Leonado Da Vinchi | Da Vinchi Illustration past copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 3 | Microscope | unknown early illustration | presumed out of copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 4 | Mercator Projection | Mercator | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 5 | Bach Counterpoint | Bach | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 6 | Stevensons Rocket | Mechanics magazine, 182 | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 7 | Sewing machine | Isaac Singer | Isaac Singer Machine contemporary photograph | Out of Copyright |

| 8 | Postage Stamp | UK Government | Copyright Free | Out of Copyright |

| 9 | Pasteuristion | Lamiot | This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. | Wikicommons |

| 10 | An 18th Century Invention – James Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny | Original Illustration | LOC | Out of copyright |

| 11 | Miners’ Safety Lamp & Portrait of Inventor Humphry Davy | unknown | About acknowledges Getty Images but Getty has no record of the image | Original out of copyright, image unknown |

| 12 | Wireless Marconi | contemporary photograph | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 13 | Teddy Bear | own photograph – eigene Aufnahme | Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 | Wikicommons |

| 14 | Talking Pictures | contemporary photograph | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 15 | Querty Keyboard | unknown | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 16 | Windscrean Wipers | contemporary photograph | Out of Copyright | Out of Copyright |

| 17 | WRIGHT FLIGHTS, FORT MYER, VA, JULY 1909. FIRST ARMY FLIGHTS; WILBUR AND ORVILLE WRIGHT, CHARLIE TAYLOR; PUTTING PLANE ON LAUNCHING RAIL | Harris & Ewing, photographer | LOC Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. | Out of Copyright |

| 18 | Fermat’s Last Theorem: Blackboard Image | James Tagg | © James Tagg | Created by James Tagg |

| 19 | Android Head | James Tagg, | Shutterstock, | Purchased by James Tagg |

| 20 | Kurt Godel | Annoymous | Copyright expired | Wikicommons |

| 21 | Alan Turing | Not recorded | UK National Portrait Gallery | Rights purchased by James Tagg/ fair use under United States copyright law. |

| 22 | Olonzo Church | unknown | Copyright expired or Princeton policy | Probably expired |

| 23 | John Bell | unknown | http://www.s9.com/Biography/Bell-John-Stewart | unattributed photo probably >25 years old |

| 24 | Matyasevich | Yuri Matyasevich | This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. | Wikicommons |

| 25 | Andrew Wiles | unknown, not references | http://plus.maths.org/content/os/issue10/features/proof4/index | Accademic use in montage |

| 26 | Conway and Kochen | Denise Applewhite | Denise Applewhite/Office of Communications | Free for non-commercial use |

| 27 | Lego Turing machine | Projet Rubens, ENS Lyon, http://graal.ens-lyon.fr/rubens/fr/gallery/ | This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. | Wikicommons |

| 28 | Kochen Specker Paradox | unknown | +Plus magazine, Rachel Thomas | fair use: Accademic, small portion |

| 29 | Hilbert’s tenth is undecidable | Matyasevich | Yuri Matyasevich | Small except, no commercial benefit |

| 30 | Julian Robinson | George M. Bergman, Berkeley | George M. Bergman, Berkeley: Oberwolfach Photo Collection, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. | Wikicommons |

| 31 | FLT Proof pdf | Andrew Wiles | Wiles Proof owned by publishing Journal of mathematics | Small except of paper for accademic use |

| 32 | Bubbles | Steve Jurvetson | This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. | Wikicommons |

| 33 | iPad Demonstration | James Tagg | © James Tagg | Created by James Tagg |

| 34 | Nebula | NASA | NASA | NASA copyright free |

| 35 | Free Universe Hypothesis Blackboard | James Tagg | © James Tagg | Created by James Tagg |

| 36 | Time line | James Tagg | © James Tagg | Created by James Tagg |

| 37 | QR Code | James Tagg | © James Tagg | Created by James Tagg |

| 38 | Poster Itself | James Tagg | © James Tagg | Created by James Tagg |